- Home

- Skin Cancer

Superficial BCC

Understanding Basal Cell Carcinoma (BCC)

Dr. Chris Irwin

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common skin cancer – about 8 in 10 of all skin cancers are BCC. It arises from the basal cells at the bottom of the epidermis (see skin diagram below). BCC often looks like a pearly or waxy bump, sometimes pink or skin-colored, with tiny blood vessels on the surface. Some BCCs instead appear as a flat, scaly reddish patch (especially on the trunk) or a white scar-like area. BCCs typically occur on sun-exposed areas such as the face, scalp, ears, neck, and arms, but also commonly on the chest and back.

The key thing about BCC is that it is usually slow-growing and highly unlikely to spread to other parts of the body. BCCs do grow locally – if left untreated for a long time, they can get quite large and cause local tissue damage – but they almost never metastasize (spread to lymph nodes or organs). In fact, BCC is often described as “locally invasive” only. It’s still a cancer and needs treatment, but it’s the kind of cancer that almost never travels in the bloodstream.

To reassure you: the vast majority of BCCs are completely curable and not life-threatening. It’s extremely rare for a basal cell cancer to become life threatening. Treating them is important to prevent disfigurement and to ensure it doesn’t eventually (in extremely rare cases) spread – this is mainly of concern on the face, where a BCC if left for a very long time can learn to follow the nerves of the face into the brain. Don’t worry about this, this is very, very rare but the main reason why we absolutely need to treat BCCs, especially on the face.

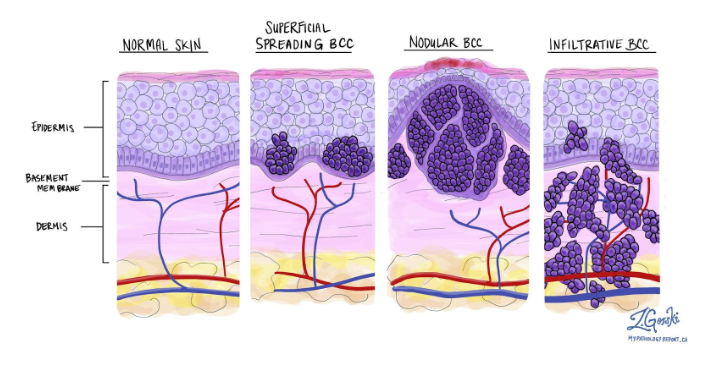

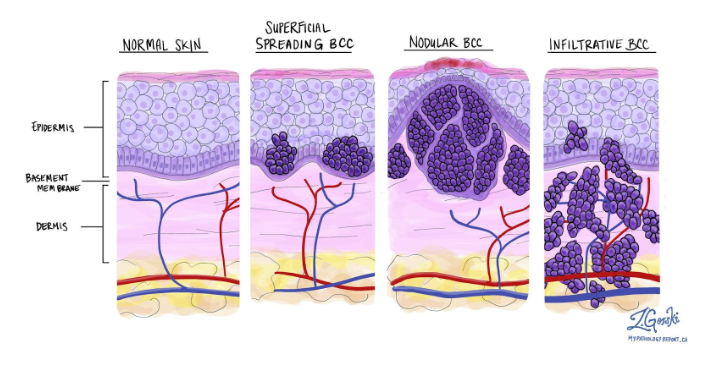

We divide BCC into subtypes mainly by how they look and grow: superficial BCC (more surface-level) and more invasive BCC types such as nodular or morpheaform/infiltrative (which grow deeper). Knowing the subtype helps in choosing the best treatment]\

Figure 1. Histological BCC.

Superficial BCC

What is it? Superficial BCC is a form of basal cell carcinoma that grows along the surface of the skin. It often appears as a flat, red or pink patch that may be scaly and have a slightly raised edge. People sometimes mistake it for eczema or psoriasis because it can be a persistent dry, scaly area.

It’s commonly found on the trunk (like the chest, back, or shoulders), but can occur elsewhere. “Superficial” means it is completely confined to the epidermis (the top layer of skin) and hasn’t yet learnt how to invade deeper into the skin.

Need for further tests? No, not for superficial BCC. Superficial BCC does not spread to lymph nodes or organs, so scans or lymph node checks are not needed. Doctors don’t routinely do blood tests or imaging for any BCC unless there’s something very unusual about it. With superficial BCC, it’s even less of a concern because it’s a mild subtype. Your treatment and follow-up skin exams are all that’s necessary.

Treatment approaches: Because superficial BCC is surface-limited, it can often be treated with less invasive methods. Treatments include:

- Topical creams: superficial BCC can often be cleared with prescription creams such as imiquimod (Aldara) applied over six weeks. Imiquimod stimulates the immune system to attack the cancer and kill the abnormal cells.

- Laser assisted Photodynamic Therapy (LA-PDT). This is one of the most common techniques we perform for sBCC. We laser ablate the cancer, then we apply a special cream that gets absorbed into any remaining cancerous cells. We then activate the cream with another special light source, that causes those cells that absorbed the cream to blow up. This is a very effective treatment with minimal downtime and good cosmetic outcomes.

- Curettage and Electrodessication: The doctor numbs the area, scrapes out the lesion and then cauterizes (burns) the base. This can work well for superficial BCCs and small nodular BCCs. It typically leaves a round, pale scar. We do this occasionally when a patient has multiple mild skin cancers and doesn’t mind the scarring for the convenience.

- Surgical excision: Superficial BCC can also be surgically cut out if needed, with a small margin of normal skin.

Prognosis: The prognosis for superficial BCC is outstanding. It is highly curable. Once treated properly, it’s unlikely to recur. There is a small chance the lesion could come back in the same spot if any cells were left behind (for example, if you treat with a cream, there’s a chance a small focus might persist and need re-treatment).

Superficial BCC has virtually no risk of metastasis (spreading), and it very rarely causes any serious damage. The main thing to remember is to protect your skin from sun to prevent future lesions and attend follow-ups (because having one BCC means you could get another in time). But overall, you should feel reassured that a superficial BCC is about as “good” as a cancer diagnosis can get in terms of prognosis – it’s not going to threaten your life and can almost always be cured with simple treatments

.

Figure 1. Histological BCC.

Invasive BCC (Nodular, Infiltrative, Morpheaform)

What is it? Invasive BCC refers to basal cell carcinomas that grow deeper into the skin (dermis and beyond) – they have learnt how to break through the dermo-epidermal junction (DEJ – the canvas like sheet that separates the epidermis from the dermis). The most common subtype here is nodular BCC, which makes up ~60% of BCCs. Nodular BCC appears as a shiny, pearly nodule or bump. It often has a dome shape with visible tiny blood vessels (telangiectasias) on it.

It can be skin-colored, pink, or even pigmented (some look like a mole). Nodular BCCs frequently develop a central ulcer or crater that might scab – sometimes called a “rodent ulcer.” These occur mostly on the head and neck (like the nose, cheeks, ears) due to sun exposure. They tend to grow slowly over time and can become quite large if untreated, but they usually remain confined to the area where they started.

Other invasive subtypes include infiltrative BCC and morpheaform (sclerosing) BCC. These are less common (5–10% of BCCs). They often appear as a flat, firm, pale or waxy scar-like area. They may not look like much on the surface (just a white or yellowish patch) but underneath they send out tentacles or roots into the skin. Their edges are not well-defined clinically (meaning it’s hard to tell where the tumor ends just by looking).

In summary, invasive BCC means the tumor is growing into the skin rather than just along the surface. But it’s important to note: “Invasive” here does not imply it has invaded other organs – it strictly refers to depth in the skin. Even invasive BCCs (nodular, infiltrative, etc.) almost never spread elsewhere; they just can infiltrate locally.

Treatment approaches: The first-line treatment for invasive BCC is surgical removal, because we want to completely eliminate the deeper roots of the tumor.

- Surgical Excision: For most nodular BCCs and many infiltrative ones, a standard excision with a margin of normal skin is performed. The area is numbed, and the surgeon cuts out the tumor. Because BCC can have microscopic extensions, usually a margin (e.g. 3-5 mm of normal skin around) is taken to be sure it’s all out. The specimen is checked by a pathologist to confirm clear margins. Excision has a cure rate in the 95–98% range for primary (new) BCCs. If margins are not clear, you may need a second surgery to get the rest, but this is straightforward.

- Off label Laser assisted Photodynamic Therapy (LA-PDT). This is one of the most common techniques we perform for sBCC. We also perform this for nodular BCC but this is an “off label” treatment not directly approved by the TGA. We laser ablate the cancer, then we apply a special cream that gets absorbed into any remaining cancerous cells. We then activate the cream with another special light source, that causes those cells that absorbed the cream to blow up. This is a very effective treatment with minimal downtime and good cosmetic outcomes.

- Curettage and Electrodessication: This technique can sometimes be used for small nodular BCCs in non-critical areas. However, for invasive BCC the cure rates with curettage alone are a bit lower than surgery, especially if the tumor extends deep. It might be used for very small BCCs (<5 mm) or superficial portions, but generally excision is preferred for definitive treatment of invasive types.

- Radiation: If surgery isn’t feasible (for example, an elderly patient who can’t tolerate surgery, or a tumor in a place like the eyelid where surgery would be difficult), radiation can be used to destroy a BCC. It is usually reserved for those special cases. Radiation can also be used after surgery if a BCC was advanced (e.g., invading bone) and there’s concern about residual cells.

Why no extra tests usually?

As with other skin cancers we discussed, routine BCC generally does not require CT/MRI scans or blood tests. The reason is that BCC almost never spreads. Doctors rely on the clinical exam. They will check and feel the area around the tumor and maybe nearby lymph nodes, but they do not expect to find BCC in lymph nodes – it’s just not how BCC behaves in 99.99% of cases. Even large or aggressive BCCs typically just do their damage locally.

Prognosis: The prognosis for invasive BCC is excellent. With proper treatment, cure rates are extremely high.

With a standard excision (surgical removal), cure rates are in the 95%+ range. If a BCC does recur (come back) at the same site, it can be re-treated, often with Mohs at that point, and still have a high likelihood of cure.

One important note: Having one BCC means you are at risk of developing more new skin cancers in the future. Your skin has shown it’s susceptible to sun damage. Statistics show that within 5 years of a first skin cancer (like BCC or SCC), about 50% of patients will develop another new skin cancer. This doesn’t mean it will definitely happen, but the odds are higher than someone who never had one. These new ones, if they occur, are usually also treatable BCCs or SCCs. Because of this risk, your doctor will want you on a regular follow-up schedule and practicing good sun protection.

The goal is to catch any new lesions early when they’re tiny. Many patients with a history of skin cancer come in every 6–12 months for a skin check. This helps maintain the excellent prognosis because any subsequent cancers are promptly addressed.

In summary, BCC (even invasive subtypes) is a very manageable condition with a superb cure rate. It requires treatment to prevent local damage, but it should not keep you up at night worrying about cancer spreading or threatening your life. You can feel confident that by working with your skin specialist and following the treatment plan, you have an overwhelming chance of being completely cured of each BCC that arises.